I

remember riding my bike down a street in Jamaica when I was about ten years

old, feeling the breeze in my hair. As I went down this street, I made

a vow to myself, "I am going to have a special life, no matter what it

takes." Ever since then I have been completely unable to live my life in

an ordinary way. As I read and examine the lives of other artists, I think

that some of us are just born this way.

One of the things that artists have in common is isolation. If you

spend a lot of time establishing common ground with other people, you are

not spending enough time having the conversation with yourself that is

necessary to get the work done before your time runs out. There seems to

be so much to do and know during my one lifetime. I certainly don't want

to spend mine watching television.

When I was seven years old my family moved from New York City to Jamaica,

West Indies. My mother offered my sister and me the choice between ballet

and art lessons. I thought ballet lessons were very silly, so I chose art.

My teacher was an American-Armenian man named Dana Basion, who came to

our house on Sundays for a four-hour lesson. He taught me to understand

color by copying and recopying Cezanne's oranges. He took short naps during

the lesson, and never came without a thermos in which he had prepared homemade

yogurt. He had moved to the island to paint, and everything he did in his

life was to make that dream possible. I liked that his life seemed to have

such purpose. His eccentric nature--which seemed to go with being an artist--appealed

to me. I had never been exposed to anything like that before in my cornflakes-for-breakfast

kind of life.

My mother read all the time and my dad went

to work, so my three siblings and I were free to explore and grow in this

tropical wilderness. Jamaica was peopled with interesting folk who looked

and talked different, and had a completely different culture from our own.

Four black Jamaicans lived in with us. We learned to speak the dialect,

and to eat saltfish and breadfruit with the natives.

This early experience shaped my whole life.

We did not have television, and you couldn't buy toys on the island. Our

entertainment was reading, inventing games, and going on trips to the "bush"

with George the gardener, in search of rare and delicious fruit. We would

climb the barbed wire fences used to keep out the goats that roamed freely--being

careful not to rip the cotton dresses we wore, or cut ourselves on the

barbs. We never returned without a basket full of mangoes, guava, akee,

ete-ote apples or "ugly fruit."

After seven years we moved to Puerto Rico to face another culture change.

There I met my second art teacher, John Hyman, a short, strange man who

was into Zen Buddhism and liked to throw knives. He turned my still-life

paintings upside down and told me to start again. He thought I was becoming

too organized for an artist. My schooling took place at a Methodist mission

school where Americans placed their children because of its excellent reputation.

I became disenchanted with the role of institutionalized religion at this

time in my life.

In my junior year in high school, my best

friend and I (both straight-A students) were permitted to apprentice with

Lindsay Daen, a famous Australian sculptor, as part of our studies. We

mixed the plaster for his giant Giacometti-esque figures. He invented strange

rituals like allowing the plaster figures to "sleep" together before they

were shipped to Spain to become bronze. I was coming to see how artists

are allowed to live in a world of their own design.

After my junior year I went straight to Goddard

College despite the protests of the missionaries, and without graduating

from high school. I was accepted because the admissions director loved

my paintings. He later came to our dorm and read us Winnie The Pooh in

a wonderful British accent.

The climate change was dramatic--in Vermont the temperature could

be forty degrees below zero for ten days at a time. I had forgotten the

snow in my childhood. Goddard had a trimester  system

and allowed students to spend some semesters away from the school. Their

sixty-year history of experimentation in progressive education allowed

students to design their own program. I had a chance to live four months

in Boston and four months in North Carolina.

system

and allowed students to spend some semesters away from the school. Their

sixty-year history of experimentation in progressive education allowed

students to design their own program. I had a chance to live four months

in Boston and four months in North Carolina.

Performances at Goddard by "The Bread and

Puppet Circus" left a lasting impression on my mind. The combination of

musical, visual, and performance art was perfected in Peter Schuman's art

in a way I have not seen duplicated in all the years since. I will never

forget the "dance of the bride" that Peter performed on six-foot stilts

while playing the violin in a floor-length white lace dress.

All of the learning I gained at Goddard has

stood by me over the years. I understood that leaving the school was only

the beginning of a lifetime's pursuit of information. There, I learned

how to learn.

I lived for three more years in Vermont, in

a big house with the "Two-Penny Circus," creating images for their publicity

and building the first "Zelda," a two-person elephant puppet. I supported

myself by making and selling block-printed greeting cards. The two-dimensional

aspect of the cards became boring after awhile, so I started making "doll

sculptures." I explored making all different kinds--ceramic, clothespin,

wire, apple, papier-mâché and cloth. At the end of five years

in Vermont, I decided to move to California. I wanted to learn how to paint,

and in my mind this was the place to do it.

I drove across the country in a VW bus to Oakland, California,

where I knew clowns from the Two Penny Circus. I put my cards and sculptures

in new stores, and started "Clown Soup," a cooperative of eight workers,

to help with the business. For the next five years we worked out of a big

warehouse. I painted "Clown Soup" on the top of the building in people-sized

letters. The name made people smile, although it confused some that we

didn't serve soup.

In 1978 I had my first child, Albee, in Oakland.

During his first year of life, Albee was carried around our workshop by

various members of Clown Soup. That was a great visual exercise for him,

and at twenty-one, he is now a very accomplished artist himself.  Life

changes when women artists make the decision to have children. The desire

to create does not go away during the years of laundry and dishes, and

one learns to juggle in order to make time to nurture one's artistic side.

Life

changes when women artists make the decision to have children. The desire

to create does not go away during the years of laundry and dishes, and

one learns to juggle in order to make time to nurture one's artistic side.

When the coop dissolved I rented my own working

gallery--where I sat on the floor and made art as people walked by. People

in the neighborhood would stop by to chat or shop. During that time I made

cards, quilts and different types of artworks that suited my mood until

I filled the gallery. A curator for the Oakland Museum chanced by and said

that this type of interaction with the public had historically been the

role of the craftsman/artist who today is unique and endangered.

After the birth of my daughter Zoe, I realized

my ten years in Oakland was up. It was time to move.

A gallery owner suggested that I move to Mendocino. I made the decision

to do so and chanced to run into a friend on a bus who knew of a house

in Elk. I rented it over the phone. With our belongings in a U-haul truck

and forty dollars to my name, my family moved to Elk. Everything would

be fine I thought, as long as I could locate a post office and daycare.

When I rounded the bend at Cuffey's Cove and saw the famous view of the

little town of Elk and the rocks, I knew I had arrived.

Daycare took awhile to locate, but Ellen and

her home daycare made single parenting possible. A short time later I met

my first husband, a third-generation logger. We spent the next five years

together. He acquainted me with the issues, the history and stories of

people who were here before me, and gave me a perspective  that

a lot of people who come here from the city never get. I came to love and

appreciate the bravery and stamina of the men and women who work in the

woods. My second daughter, Larkin, was born in 1989. When my husband's

mother tragically died of cancer at age fifty-three, I saw that the constant

hardship of that culture and life destroys people. I couldn't continue

to live this way.

that

a lot of people who come here from the city never get. I came to love and

appreciate the bravery and stamina of the men and women who work in the

woods. My second daughter, Larkin, was born in 1989. When my husband's

mother tragically died of cancer at age fifty-three, I saw that the constant

hardship of that culture and life destroys people. I couldn't continue

to live this way.

I became a single mom again, and despite the hassles of

earning money to support us I decided to paint. I collected my last ounce

of strength, and began painting one afternoon a week. The work went well

and was satisfying.

In 1992 I met my current husband, Steve. We

built a house together in Elk. My time since then has been divided between

my artwork, community service and raising my three children.

People ask me how I find the time to do so much. It takes a lot of

discipline and single resolve. I create plans, make lists and schedule

everything. I never stay still or sit down. About eight years ago I stopped

watching television--then later gave up videos. As I narrowed my activities

I was able to find time for the reading and studies that are necessary

for my work to continue. If I didn't feel that my understanding was growing

I would be very unhappy. Because of this my children learned to be very

independent, and extremely good cooks. Preparing food takes more time than

I am willing to give it.

Shortly after moving to the coast, the local community center became

the center of my social life. Five years out of the past eight I supervised

"Great Day in Elk," the big yearly fundraiser that allows the center to

pay its bills. Four years ago I decided to push through Del Wilcox's vision

for a theater add-on to the center. I put a lot of time into that project,

and managed the core committee of women who wrote grants and raised money

to build the Del Wilcox Theater. The town now has a well-equipped little

theater to call its own. The efforts in this direction have been very rewarding

as I have watched the process that occurs when a group donates its time

and begins to have a feeling of ownership and pride in its community. This

is the best way to grow a town.

Meanwhile I began selling my paintings. The first year, I sold one

for seventy-five dollars. The next year two sold at double that price.

This pattern has continued.

Artists tend to be very isolated except when they sell something to a customer.

When I joined North Coast Artists in 1994, I had been working alone for

over twenty years. Joining this group was a big step in giving me company

in my pursuits. The shows I put together over the next five years have

brought me great satisfaction and a fair amount of recognition in the local

art scene.

Artists tend to be very isolated except when they sell something to a customer.

When I joined North Coast Artists in 1994, I had been working alone for

over twenty years. Joining this group was a big step in giving me company

in my pursuits. The shows I put together over the next five years have

brought me great satisfaction and a fair amount of recognition in the local

art scene.

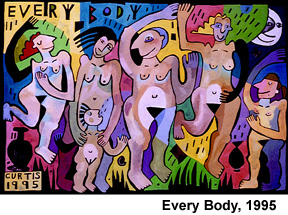

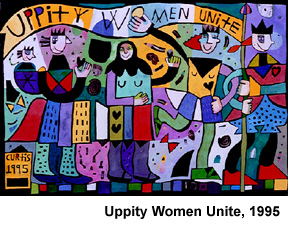

My first theme show (1995) was called "Tea

Party for Angels," and dealt with issues around women and work. I wanted

to express what an incredible challenge it is for women to raise children,

make a living, and have time to be creative. This show was joyfully created

in an unheated room that a friend gave me in which to paint--where I sat

wrapped in blankets with a space heater by my feet. I made ten paintings

there, using the gouache and India-resist method that I called "window

painting," in which I left lots of little boxes or windows that show the

layer of paint underneath. The piece on this cover of Sojourn, "Best Mom,"

came from that show. The image is a reminder of the many years when I was

trying to go forward in life with one child on my back  and

another little one in hand. My young son at the time wrote me a card with

the words "best mom." That meant a lot to me.

and

another little one in hand. My young son at the time wrote me a card with

the words "best mom." That meant a lot to me.

After the success of the first show, I developed

a great passion for creating theme shows. Since the frames cost money and

I was afraid to take the financial risk, people advised me to apply for

a grant. I applied to an East Coast organization that was not interested

in my work. It was hard for me to deal with their rejection, but once I

accepted that I could not depend on the establishment to make shows happen

for me, I decided to take the risk myself.

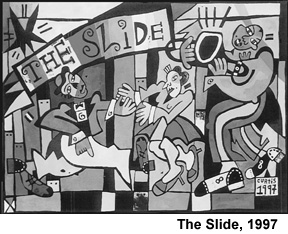

It took a year and a half to get the time

and money for my next show (1997), "Lindy Hop: A Time to Shine." This show

was about people's need to have a "moment in the sun." It was very popular.

People from Berkeley and San Francisco came and bought pieces for their

collections, and some bought them as "investments." A lot of this work

was reproduced on web pages, which brought me work from all over the country.

I did some work with Neuro-Linguistic Programming

(NLP) in winter of 1998, that started changing me as an artist and as a

person. I put together a ten-piece show, "Open Doors," in May of that year,

in celebration of my new learning. Since it sold out in  four

months, I thought it was ridiculous to wait so long between shows. It seemed

that the lesson was that people like and buy my art. Producing the paintings

is a way of learning and teaching myself to be a better artist. To be paid

to learn! This is what I most wanted.

four

months, I thought it was ridiculous to wait so long between shows. It seemed

that the lesson was that people like and buy my art. Producing the paintings

is a way of learning and teaching myself to be a better artist. To be paid

to learn! This is what I most wanted.

After the Lindy Hop success, friends had wanted

me to do a jazz show. I didn't know much about jazz, but I said OK. It

took me six months of listening to become a jazz lover. February, 1999,

I opened "Jazz: Call/Recall." The concept had to do with someone making

a call, and another responding. I was recognizing my own need to be influenced

by the work of others while recognizing this trend in all creative endeavors.

After taking a class from Janet Lipkin at

the Mendocino Arts Center in printmaking (July 1998), I became obsessed

with creating monoprints and decided to use this technique for a number

of images in the jazz show. This new direction was risky because people

were used to my work looking a certain way, and I can't afford for my shows

not to sell. The public was very impressed with what they termed the "muted

tones." But as it turned out, I sold only half the work and now have to

find a way to sell what remains.

This week is designated for creating the ideas for the last five pieces

of a show I will call "Conversations." I am making playful cartoon-like

mono-prints illustrating themes that recur in artist's lives. I put in

months of reading of artists like e.e. cummings, Ben Shahn, Rainer Maria

Rilke and Corita Kent to understand more about myself and some of the similarities

that artists share. I also want to continue my exploration of new techniques

by using collage and cut-outs in this series. This show will open at Cafe

Prima on Laurel Street in Fort Bragg, in November and December.

As I work on each show, I read books and keep

a journal. The people who come to the show can share in my process by reading

this material. I am especially pleased when other journal writers come

to the show and copy passages into their own journals. My journal includes

passages I read that inspire me. I once went to a show in Los Angeles by

Annette Messenger, a French artist. Her journals (included in the show)

were housed in a glass case, and I couldn't read them. I thought, "Of what

use is this?"

My last show in Mendocino County, planned for February of 2000,

will bring closure to my time here and will be dedicated to the community

of Elk. It will translate into images some of the stories told to me over

the past fifteen years by the people here. I am hoping to incorporate a

performance piece into the show using the Del Wilcox Theater. The ideas

for this work are beginning to flood my mind. This is how it all begins.

In June 2000 I leave for the East Coast. My

fifteen years is over. I spent many years here learning to paint,

raising children and doing community work. Now I wish to refocus my energies

toward other goals. I am still a long way from being the artist I envision.

That dream goes back thirty-six years when I made a promise to myself as

a child.

In my current focus on the lives of

artists, I have found that those who achieve the most satisfaction in producing

significant work never stop growing, changing and asking why. Personally,

I have felt that when I become too comfortable, it is time to shake up

my life in order to keep learning at the highest level possible.

Kay Curtis has been selling her soft sculptures and block-printed

cards across the country for the past thirty years through her businesses

called "That's Irrelephant" and "Clown Soup." She has been painting for

the past ten years. This work can be seen at the North Coast Artists Gallery

in Fort Bragg. You can make and appointment to visit her studio by calling

707-877-3564. She can also be contacted by e-mail at kcurtis@mcn.org or

by writing her at P.O. Box 53, Elk, CA 95432.