It came down to this--the call to journey became

so intense that my life was disintegrating. A lifetime of self-concepts

grown from community living, personal goals I had long cherished, and all

that I had taken for granted about myself rang hollow. I had no other choice.

The archetypal hero's journey always begins with an irresistible call that

takes you by the collar and leads you out of your former life. I had waited

a long time to travel to Europe, the land of my ancestors. I didn't know

exactly where I was going, when I would be back, or whether I would be

back. But I trusted myself to enter the unknown, which is a very valuable

place from which to begin a journey.

My father was a primary influence

in my early spiritual development. He taught me that everything has a soul,

and that I could use my dreams and other symbols I encountered in life

to understand my own psychic growth. Dad would get down on my level and

play, bringing my stuffed animals to life, taking them on adventures and

encouraging me to tell stories about them. When I was five, I had a couple

of imaginary friends called Oma and Opa. To me they were two woman schoolteachers

who guided my stuffed animals on adventures. I would tell Dad these stories,

and he would sometimes write them down. This process fostered my creativity

and trust in my inner world.

Dad's encouragement continued

in my early teens. We lived in a small house in Talmage where we created

what we called "altars." These tiny scenes, made from interesting rocks,

dried frogs, plastic cowboys and Indians, and all sorts of found objects

became ever-evolving stories about our lives. Sometimes we shared these

private stories with each other, and sometimes not. We had a silent understanding

about the sanctity of our altars, and we allowed the process to arise in

natural rhythm. I learned I could trust my creative unconscious to provide

me with the images I needed for my individuation.

Growing up on the land, in the

Greenfield Ranch community near Ukiah, gave me a strong spiritual relationship

with nature. I was free to roam the open oak and fir woodlands, ridges

and creek beds of the California Coastal Range, and it was natural for

me to experience Spirit in the land. But as a young woman I found

I was in conflict about how to relate authentically to this land since

the ancestors of the land here are primarily Native American. Though I

experienced my primary relationship to Spirit through the land, I had never

wanted to assume a Native American path because it didn't feel like mine.

My ancestors were European, and I longed to connect with their traditions

and sense of place.

When I was eighteen I started an apprenticeship

in Wicca. In the middle 1980s, the idea of honoring the Goddess was beginning

to grow, and in this spiritual community I had a framework for discovering

my power as a woman. Claiming historical rights to nature worship, I adopted

the title "witch." This gave me a sense of belonging, and obscured what

I experienced as the jarring heartache of my ancestral discontinuity. A

wondrous European tradition rich in mystery and lore opened up for me,

but the land I lived on spoke another history. I wondered how to bridge

this gap.

Several years ago, I had a dream that I was

walking down the dirt road to the front gate of Greenfield Ranch. I came

upon seven white ravens, and as they took off in flight I flew with them.

Suddenly I was in a European country, looking out the window of a train

at rolling green hills. It seemed as if the Spirit of the land I love here

was taking me to see the source of my ancestry there. In another dream,

I was led to an oak on the Greenfield common land. In the oak was a door,

and inside the door was a little green person. I entered, and was transported

immediately to the British Isles. Symbolically I was taken through that

door to the mysteries of the Otherworld.

Before I left home I was studying the Grail Mysteries and the ancient

story of Perceval and the Fisher King: Perceval, traveling in the Otherworld,

is brought to the castle of the wounded Fisher King, whose kingdom is a

wasteland. Perceval beholds strange sacred objects--the Holy Grail and the

Bleeding Lance--and though he wonders about them, he doesn't ask any questions.

Thus he sets in motion a series of events that compels the knights of King

Arthur on a quest to ask the correct Grail question in order to heal the

Fisher King and his kingdom.

This story illustrates an historic idea that the well-being

of the king is a reflection of the health or suffering of the land he rules.The

divine rite of the king to rule is dependent upon his favorable relationship

to the Spirit of the land. Sovereignty (self-rulership of nation,

tribe or individual), is a name for an ancient British earth goddess.

It is She who recognizes the sovereignty of rightful rulership and She

who retracts it.

A few years ago, on Greenfield, there was

an ongoing debate about the spring on our common land. We argued

as whether or not to regard it as a "sacred spring". Underlying this question

was the problem of our relationship to it.

The sacred spring is another symbol for the

Holy Grail--The feminine vessel, source of nourishment and inspiration,

source of rebirth. How we interact with this source represents the

state of our personal and collective relationship with the land. Asking

our "Grail question" is the quest for sovereignty, which can be understood

as seeking rightful relationship with inner and outer nature, in

blessing for empowered self-governance. This is a mythic quest: eternally

of the Other world, it engages both the individual and the collective.

The entire court of King Arthur is called; yet each knight in his quest

enters the forest at a different point.

I finally answered the call and headed for Europe. As I traveled I

went deeply into myself and continually asked, "What do I need to do next?"

I would find myself literally at a crossroads and ask, "Where do I need

to go?" My tendency to mentally control my life gradually lessened as I

allowed myself to be guided. As I traveled, I was reminded of issues within

myself as well as of issues affecting my community at home. I wondered,

"How does this apply to my land or my community?" Questions would form

in my mind; then pieces of information, reflections of the problem, would

soon present themselves through events, dreams, and people that I met.

I noticed that even the e-mails I received from home often reflected the

same set of questions I was exploring. Through traveling, I was connecting

with my people at home; I realized a thread of connection was keeping us

together the whole time.

|

The village of my ancestors, with its little, abandoned Evangelische

Kirche on the hill and the graveyard just cresting it resonated to me as

if I were a prodigal daughter, whispering love in the breath of the wild

rose-scented breeze. |

In Ireland I met an extended pagan family called the Grove of Sinann.

They tend a beautiful Celtic tree circle, a labyrinth and other ritual

spaces along the headwaters of the Shannon River--the legendary site of

the sacred Spring of Wisdom and Everlasting Life. There I met Adge, whose

motorcycle leathers and big red beard reminded me of the hippies of my

childhood. His caravan was plastered with funny, cryptic pagan messages

made from newspaper clippings. He had altars of embroidered cloth, painted

deer skulls and beautifully handcrafted magical tools that reminded me

of Greenfield in the 1970s. We spent hours in the rain-soaked Irish

winter drinking tea and visiting the ancient sites of the Faery.

Adge told me that the mythological Irish Faery,

or Tuatha de Danann--people of the goddess Danu--were actually late Bronze-Age

people who built round houses and possibly erected a lot of the old stone

circles, cairns and dolmens. In legend, they were invaded by Iron-Age Celts.

According to myth, the Tuatha were conquered in a contest of magical powers

won by the legendary druid, Amergin the Bard. As a result, they disembodied

and became one with the land, which is why faeries are said to guard places

of power in the Irish landscape like hawthorn trees, sacred wells, cairns

and caves. The archaeological remains of the Tuatha's round houses are

called "faery raths" (forts). Irish farmers usually plow carefully around

hawthorn trees in the fields lest they unleash the fury of "the good people."

A respect for the ancestors of the land survives through the spirits of

the Faery.

Adge introduced me to Joe Mullally, a professional diviner who lives

in the Wicklow Mountains south of Dublin. He is paid to visit houses and

other areas that have magnetic "disturbances," and suss them out. These

disturbances manifest as sickness, arguments or other ailments. The cause

can be water lines or ley lines; or the house may be sitting along a path

of ancient stone monuments, of which there are plenty in Ireland. The spirits

of the place might be upset about too much development; or there may be

restless human spirits that died in battle at that spot.

Through shamanic journeying, Joe receives

information about how to release "the situation," as he calls it. He is

a wonderful storyteller, with big Coke-bottle glasses. With a magnified

twinkle in his eye, he'd tease me about how the instructions he received

sometimes had more to do with his own mother than with clearing something

about an ancient battle scene. With a hearty Irish chortle he impishly

intoned, "Ah, but maybe it's all me own figaery!" (a figment of his imagination).

I finally had to ask him, "Joe, if a site just reflects back to you what

you need to work on in your own life, how do you know that the remedy you

find for the place will work for other people?" The look on his face gave

me my answer. He looked as though he were pleased that I had finally asked

it. He said, "It just does."

Joe says anyone who makes a relationship

with a place and listens to it with an open heart and mind will have a

personal experience with the spirits of that place. He explained

that if there's a disturbance in the energy of that place, it will draw

out disturbance on the inner levels of the diviner. If the diviner can

clear the inner disturbance, the landscape will be released as well. Joe

said this clearing doesn't necessarily take place immediately, so he commits

himself, Spirit to Spirit, to that place and those relationships beyond

time. The fact is that we are all interconnected--the deep personal work

of one is able to send shivers through the web of connection, thereby altering

the entire landscape of relationships.

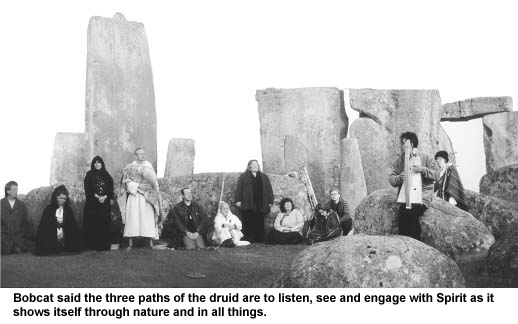

Through Joe Mullally I met Emma Restall Orr, or "Bobcat," who introduced

me to druidry--the Celtic religion of an order of priests in ancient Gaul

and Britain--and the ways it is practiced today. Emma is joint chief of

the British Druid Order, and the author of Spirits of the Sacred Grove:

The World of a Druid Priestess and The Principles of Druidry. We met at

her home in the Midlands of England after a druidic ceremony--a Gorsedd--at

Avebury stone circle. As we walked through the countryside we felt an immediate

kinship, which grew over the next two months into a friendship and spiritual

sisterhood.

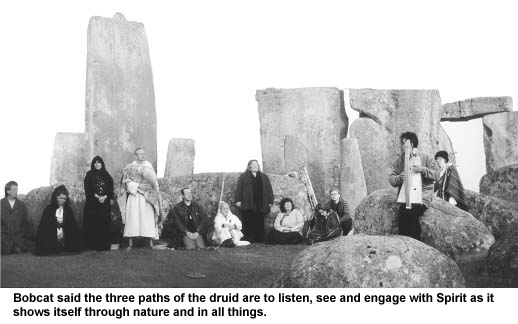

Bobcat recognized and enhanced my native genetic

inheritance of spiritual relationship to land. She said the three paths

of the druid are to listen, see and engage with Spirit as it shows itself

through nature and in all things. The classical texts relate three layers

of druidic training. The bard (of the ancient Celtic order of minstrel

poets) listens to Spirit, transforming inspiration into works of art, song,

poetry and story; creative works are released back into the world as offerings.

The ovate (second level druid) seeks true vision through nature, Spirit

and time, using clairvoyance as divination and healing. The druid

combines these skills to walk with Spirit, entering the lands of the Otherworld

at will, in a state of divine inspiration.

| Soft mist swirled around the sun as it rose gently behind the heelstone.

A druid's prayer, called forth in Gaelic, sent shivers through my bones

as light slowly opened into the reverberating sarsens (standing stones).

There was such a sense of simplicity among us. |

|

Awen is the Welsh word for "inspiration" or "flowing Spirit." In the

Otherworld, nine maidens tend the Cauldron of Cerridwen the Crone, cooling

her primal brew with their virgin breath. The steam rising from this ancient

vessel is the awen, the divine creative energy. This divine inspiration

finds expression in the traditional paths of the bard, ovate and druid

in the forms of poetry, prophecy and shape-shifting. Druidic ritual focuses

on developing creative relationship with the source of inspiration, and

then offering the fruits of that inspiration back to the ancestors, the

gods and goddesses and the spirits of place.

Druidry is different from Wicca, which centers

on using ceremonial intention to focus will for magical change. I realized

I had been limiting myself by my desire to control outcomes rather than

surrendering to the creative process. I remembered the natural wisdom of

my free-flowing youthful altars, and knew it as awen at work in my life.

My heart flew home to the beloved land of my childhood, remembering the

cyclic intimacy of familiar seasons. The Spirit of the land we now call

Greenfield ebbs and flows in a sentient matrix of relationships. I realized

I had always known this.

Ancestors of blood and Spirit travel with

us, in our bones. Yet breathing in the landscape are the spirits of place.

How, I wondered, do I honor the spirits of the place I love in my spiritual

practice? How can I and my community recognize and honor the ancestors

of this Native American land in our quest for a rightful relationship with

Sovereignty?

At this point in my trip, my mother joined me. She brought me to the

tiny village in Transylvania (across from Russia near the Black Sea) where

her grandparents, Thomas and Maria Nikolaus, grew up. We deepened into

the journey together. My great-grandparents were Saxon Germans who immigrated

to the U.S. in 1912 from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Before going to Transylvania,

my mother and I met my great-grandfather's cousin and his wife in Germany.

Michael Nikolaus, ninety-eight, and Katarina, ninety-two, embraced us immediately

as dear relatives. Their granddaughter, Ulrike, translated for us. Imagine

my surprise when she referred to them as Oma and Opa, the German nicknames

for grandmother and grandfather--the same names I'd given my imaginary childhood

friends!

Michael told us stories of the village

called Haschagen, where he and Thomas and Maria grew up, and where their

families had lived as farmers for generations. He told us how in 1945 the

Romanians and Russians came to their house early one morning. At gunpoint,

they demanded Michael's seventeen-year-old daughter be taken for forced

labor. He knew the Romanian schoolteacher who acted as guide to the Russian

soldiers, so he begged the man to leave his daughter and take him in her

place. Michael was taken in a cattle car to Russia. For five years

he lived on sorrel and cucumber soup, in an Ukrainian labor camp, thinking

all the time of Katarina. Tears welled up in his eyes as he spoke of this--he

had not known if he would ever see her again. I looked over at Katarina

and asked, "Were you happy to see him when he returned?" She needed no

translation to understand me and replied immediately, her jaw working and

eyes brimming with emotion, "Ya, Ya!"

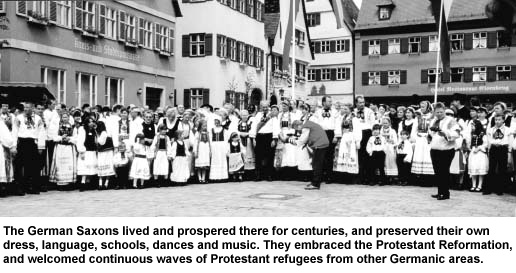

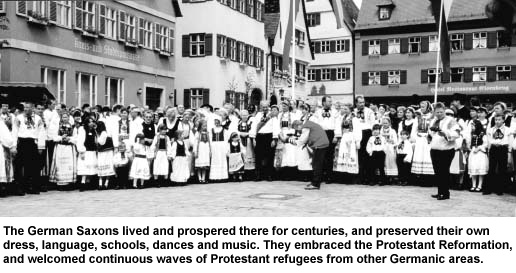

The Saxons came to Transylvania in the twelfth century,

at the invitation of a Hungarian king. They built seven fortresses throughout

the Carpathian Mountains in an area called the Siebenburgen, to keep out

the invading Turks. They lived and prospered there for centuries, and preserved

their own dress, language, schools, dances and music. They embraced the

Protestant Reformation, and welcomed continuous waves of Protestant refugees

from other Germanic areas.

When the Austro-Hungarian Empire

fell during World War I, the Siebenburgen was turned over to Romania. During

World War II the Romanian king sided with Hitler, and many Saxons were

given wartime jobs in the Nazi SS. After the war, as happened to Michael,

every Saxon German between seventeen and forty-seven was deported to Russian

forced-labor camps. Those who refused or tried to hide were shot, sometimes

in front of their communities as an example to other would-be resisters.

Many died during the long transport, and many never returned. The elderly

and the young were left to survive on what they could. Most were forced

to leave their farms to find jobs in the larger cities. Gypsies, so they

say, stole from the abandoned houses and farms. The people who survived

to return, five years later, came home to houses that had been pillaged,

in a country that was now under Communist rule.

The orchards and fields plowed, planted and tended by

generations of my ancestors now belonged to the Communist government. The

people were allowed only a small patch of land for household gardening,

and they were forbidden from congregating at the commons where they used

to gather firewood, play music and dance.

Mom and I attended the annual

reunion of the "Siebenburgen Sachsisches" near Munich, where we got to

see the dances and costumes of our ancestors brought to life before our

eyes. Tears filled my eyes as I beheld their cultural pride, the beauty

of their art, and their close family relationships. I was overcome to realize

that these people had survived together through all they had endured. I

was saddened, though, to hear from those Saxons I asked, that they never

want to return to Romania. Their faces hardened, and they said firmly,

"There is nothing in Romania." Only the elderly Michael and Katarina nodded

when we asked if they missed the Siebenburgen. Michael gripped my mother's

hand and softly began to sing an old song of love for the land.

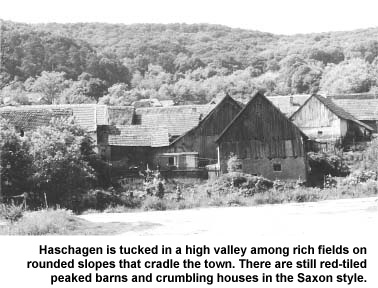

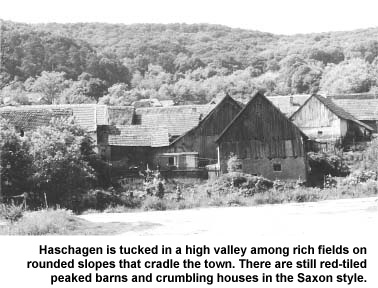

The little village of Haschagen is tucked in a high valley among rich

fields on rounded slopes that cradle the town. There are still red-tiled

peaked barns and crumbling houses in the Saxon style. Horse-drawn plows

cultivate the single furrows that etch the warm shoulders of the mountains.

I clambered through the dirt tracks of the village, past the cows and chickens

to the woods above the fields. The woods were dark and thick, with muddy

paths that surely led to other villages. Entranced, I imagined ancient

horsehooves beating rhythms for young riders seeking adventure in adjacent

valleys. One chilling breeze spoke of those who tried in vain to hide from

the Russian soldiers. Listening deeper, I heard the soft tones of trysting

lovers beneath alder and oak; and in my mind's eye I saw a grandmother

stooping to gather wild ginger, false Solomon's seal and nettles. In the

center of a ring of oaks I saw a hawthorn tree nodding her welcome.

Stepping into a clearing, my eyes beheld the wide

expanse of a horizon I knew was traced by the loving eyes of generations

upon generations of my own foremothers and forefathers. A strange sensation

crept over me. I was amazed that I could feel lifetimes of love for a land

in a first glance. Wild comfrey grew at my feet. I wondered, "How is it

that I know this place?" I felt as if I could almost see Saxon maidens

in richly embroidered clothing standing with me, but in another century,

themselves only dimly aware of the river of blood and time connecting us.

Below me, farms now owned by Romanians chattered

and sang the same old songs of horses, dogs and roosters. The Saxons were

gone from their land, whiffed away by one strong puff of fate. The village

of my ancestors, with its little, abandoned Evangelische Kirche on the

hill and the graveyard just cresting it resonated to me as if I were a

prodigal daughter, whispering love in the breath of the wild rose-scented

breeze.

Through my eyes I now knew my ancestors' love for their land, and the

acute loss of it stung my heart. I did not fully feel the grief of their

loss until that moment when I stood with them and felt their cruel but

random and blameless destiny. Often in childhood I had visually swept the

California landscape clean of the twentieth century, trying to imagine

the world of native peoples. I realized that people all over the world

have been torn from the ridges and valleys they loved for centuries. The

gift I received from my Sachsisches ancestors is the knowledge of this

love, and the imperative to actualize it. Their message is "Do not disregard

the beauty and power of the land; and honor the people who came before,

for they are still here." In some strange way, my ancestors can relive

their love for Haschagen through me, in my love for Greenfield.

The last stage of my journey, was attending the British Druid Order's

Midsummer Rite in Stonehenge, with Bobcat and her fellow British Druid

Order chief, Greywolf. It had been a tense week leading up to the rite.

Since the 1970s, there has been a free festival at Stonehenge on summer

solstice, and days before June 21st word went out on the Internet that

a rave was planned at Stonehenge. The rave turned out to be a riot. Greywolf

and Bobcat, who had been in attendance, did their best to guide the flood

of media attention away from the conclusion that the spiritual tradition

of Druidry had been denigrated to drunken, desecrating revelry. The worldwide

news was depicting crazed young men dancing atop the ancient lintels. Bobcat

was exhausted when she returned home, and for a time we feared that our

special-access permit would be revoked.

But in the predawn of midsummer's day, we arrived as planned

at Stonehenge. A soothing blanket of mist spread through the plain.

I jumped with surprise as suddenly from the car window the ancient stone

circle popped into view. Mist tightened around the darkened stones as if

drawn in by invisible beings. I had the immediate sense that Stonehenge

was cleansing itself.

Our approach was silent and careful. We were

being so tender in our entrance into the circle that Bobcat had to prod

us along to gather in time for the sunrise alignment. Soft mist swirled

around the sun as it rose gently behind the heelstone. A druid's prayer,

called forth in Gaelic, sent shivers through my bones as light slowly opened

into the reverberating sarsens (standing stones). There was such a sense

of simplicity among us. I recognized that the long journey I had begun

years before, in my dreams as a young woman, was finding completion in

a homecoming of real time, real space and real love.

The British Druid Order is one of the largest international orders

of Druidry. They can be contacted on the Worldwide Web at:

http://www.druidorder.demon.co.uk

Joe and Una Mullally facilitate divining and Earth-healing workshops

at ANAM Grove. They can be contacted by writing to: ANAM, Manor Kilbride,

County, Wicklow, Republic of Ireland or by email: earthwise@tinet.ie

The Grove of Sinann holds seasonal workshops in Celtic mythology, and

can be contacted via email at sinann@iol.ie, or by writing to: Teach Sinann,

Keshkerrigan, Carrick-on-Shannon, County, Leitrim, Republic of Ireland

The British Druid Order is one of the largest international orders

of Druidry. They can be contacted on the Worldwide Web at:

The British Druid Order is one of the largest international orders

of Druidry. They can be contacted on the Worldwide Web at: