|

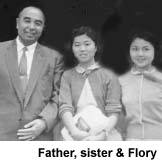

I was born in mainland China and moved to Taiwan when I was thirteen years

old, then to the United States after high sdad

was an official in the Chinese government, but also a writer and a scholar.

He surrounded me with books. Since I was nurtured that way, I also wanted

to be a writer.

I received a scholarship to a Catholic University

in Florida, where I majored in secondary education and minored in literature.

This was tough for me--especially English literature. Most of the students

had read so many books. I would go to the library and read synopses to

catch up. I felt that I could not express myself well enough in English,

and my Chinese wasn't that good either.

I was married immediately after graduation. My husband was Chinese,

and had lived in America since his teenage years. He had little Chinese

indoctrination, and seldom spoke Chinese. His father was educated in Belgium,

and was involved in diplomatic circles as Taiwan's ambassador to the Vatican.

My father was a Confucian scholar, so

my background was much more instilled with tradition. He was very responsible

to his job and his country, and my mom was totally involved with home and

family.

In my marriage I had such devotion and

one-mindedness carrying on the Confucian tradition of my family without

ever examining or questioning it. I never had any independence. Do you

accept what is passed on to you without ever reexamining it? I did. I was

100% wife, 100% mother, 100% daughter-in-law. I took food to my husband

at work, entertained his company people by cooking gourmet Chinese food,

mowed a three-acre lawn, took care of a garden, kept the house spic-and-span,

and then dressed up to entertain houseguests. Afterwards I did more dishes,

mopped the floor and cleaned up. I took care of our three children, trying

to nurture them into whole human beings. I read them poetry to go to sleep,

played them music, taught them Chinese writing, took them swimming, and

so on. When my husband's father was sick, I took care of him. Yet, there

was such a feeling of loneliness inside me.

I wanted to do something for myself, so during

the last two years of my marriage I went to a New Jersey YMCA twice a week,

in the evenings, to draw and paint. That was the beginning of my art. I

was still very starry-eyed.

Around the sixth year of my marriage, I sensed something was going

wrong. My husband was seldom home. He was always busy and working overtime.

Often, I would wait up until two or three o'clock in the morning, worried

that he might have fallen asleep while driving. Little did I realize that

he was having an affair with a co-worker--an Italian woman who also did

babysitting for us. Everybody knew but me.

This affair went on for two years. Buddhism

says that stupidity and ignorance are stumbling blocks to everything. Unless

you clear your mind, you can't resolve any problems. It was this way for

me. I was living a good traditional life. The marriage counselor asked

my husband, "Are you having an affair?" He said, "No," and added, "She

is a perfect wife." The counselor said, "Well, what's the problem then?"

There was nothing the counselor could do. John's boss and partners said,

"You can't do that to Flory. You'd better send Anna back to Italy." They

had a farewell party for her and wanted me to sing at her party.

Since I didn't know the whole story, I did sing for her.

An affair gets hottest when it is forbidden and

when people are separated. The more the fruit is forbidden, the more attractive

it becomes. A wife is not attractive because she is there every day. At

some point, Anna came back to the United States. The night my husband told

me he was in love, I guessed who it was.

I was deeply hurt and wanted to get away, so the

next day I left for art school--the Art Student's League in New York City.

I realized that there would be no way for me to raise three children, physically

or financially, as an art student. I also knew that for the children, security

is of foremost importance. My husband had a comfortable lifestyle, and

the children had playmates and security with him. They knew Anna, their

babysitter, well, so I asked and they both consented to care for the children.

Shortly after I settled in school, I swallowed my

hurt and pride and called John. I told him that this breakup did not concern

only the two of us; it would have lifelong consequences for the children.

Would he reconsider? If he was willing, I'd come home and we could start

over. John informed me that Anna was pregnant, and they planned to get

married.

What did I do? Why was this happening to me?

I was doing 100% of everything. This betrayal caused me to ask very deep

questions about what love and filiality are. I began to question everything

I was taught.

I was forced to leave my children. This would be painful for any woman,

but I feel that my salvation was the strong character of the family I came

from. Many times the Chinese were overwhelmed by the bombing, and the soldiers

wanted to run away. My father  would

set the table right in the middle of the open skylight while the bombing

was going on. To stabilize the soldiers, he would say, "I'm here. Everything

is okay." He was gutsy. My mom had become a spy. My father's army was ill-equipped

and there was malaria, so she went back to Shanghai--which was occupied

by the Japanese--to get contributions of money to buy medicine and mosquito

nets for the soldiers. The Japanese could have arrested and killed her. would

set the table right in the middle of the open skylight while the bombing

was going on. To stabilize the soldiers, he would say, "I'm here. Everything

is okay." He was gutsy. My mom had become a spy. My father's army was ill-equipped

and there was malaria, so she went back to Shanghai--which was occupied

by the Japanese--to get contributions of money to buy medicine and mosquito

nets for the soldiers. The Japanese could have arrested and killed her.

Although I was gentle and docile, these strong

characteristics were in me too. I didn't cry or complain. I wanted to be

an artist, and I made a decision to go forward and not look back. Of course,

I missed my children terribly. I had visiting rights with them for the

first year, but then I was told that the children were being torn between

two families. I wanted things to work out for them, and decided to take

the back seat so they would have a better life. They were told, "Your mother

doesn't want you. She abandoned you." That's the only story they knew.

You ask me why they did this? I asked why

too. For reasons mostly unknown, human beings tend to do a lot of foolish

things. The stepmother was very insecure, and couldn't believe John would

divorce me and marry her. She feared that someday the children would all

come back to me. This painful experience has made me dig down deeper to

think about human relationships and true realities.

I was close to thirty years old when I began to study sculpture at

the Art Student's League. A lot of my schoolmates were half my age. But

I had a vision, and I worked very hard. At the end of my fourth year, I

won the coveted McDowell traveling scholarship. In twenty-eight years,

this award had never been won by a sculptor--only by painters.

I left for Europe, made quick trips to centers

of art, and soon realized that I couldn't become a sculptor by just looking

around; I must work. I decided to go to Carrara, Italy, to the quarry where

Michelangelo had gotten his marble. My scholarship gave me enough money

to stay and work there for a couple of years. I rented space, watched the

carvers, and learned the best way to carve; what is good stone and what

is a cooked stone, and more  importantly

how to move large pieces. The renowned sculptor Jacques Liptchitz was there

at the time. We asked him, "Maestro, can you teach us to be good sculptors?"

He said, "You can learn whatever the foundry casters and artisans can teach--how

to handle stone, how to carve it and how to cast, but the rest can't be

taught." That was a good lesson. importantly

how to move large pieces. The renowned sculptor Jacques Liptchitz was there

at the time. We asked him, "Maestro, can you teach us to be good sculptors?"

He said, "You can learn whatever the foundry casters and artisans can teach--how

to handle stone, how to carve it and how to cast, but the rest can't be

taught." That was a good lesson.

In Taiwan I had gone to the best girls' high

school. We were studious and outstanding students, and were accepted at

the best colleges and universities. At our reunion, I saw that most of

these women were professors now in fields like computer science, chemistry,

biology, and so on. It was like listening to broken records. I told them,

"You guys all ended up doing the same things you were good at from the

beginning. Am I glad that I broke the mold. At least one of us is a stone

chiseler."

I could never have dreamed of doing this,

because people who work with their hands are looked down upon in Chinese

tradition. Handwork is considered labor, not art, and the Chinese remember

very few of their sculptors. Yet sculpture has turned out to be my salvation.

It was a tough road, but now I am really thankful. My  whole

life has changed. I have become a good craftsman, and I am proud to be

able to deal with all facets of mechanics and materials. whole

life has changed. I have become a good craftsman, and I am proud to be

able to deal with all facets of mechanics and materials.

When I came back from Europe I had a one-woman show

in New York City. I also remarried. My new husband was a construction manager

and worked on government projects--building housing, hospitals and schools,

etc. Through him I was happy to have learned much about the mechanics and

construction of things. From that time on I have devoted myself totally

to my work.

I did stone carving for a full five years, and missed my children terribly.

The images I carved were about mother and child, family, security, warm

wind, and love. Later I realized that reality is forever changing. There

is no bottom line. That started to change the direction of my work.

I enjoyed going to watch modern dance, and noticed

that the movements and interplay of the dancers made patterns of changing

colors and forms. From this inspiration, I made a black and white  chest

of drawers and painted it inside and out. I had a one-person show at So

Ho in New York City around this theme of folding and unfolding images.

When the audience moved the drawers, their different associations created

a variety of patterns. chest

of drawers and painted it inside and out. I had a one-person show at So

Ho in New York City around this theme of folding and unfolding images.

When the audience moved the drawers, their different associations created

a variety of patterns.

In 1978, I was invited to set up and run the sculpture

department at Dharma Realm Buddhist University in the City of Ten Thousand

Buddhas in Talmage, California. My husband and I sold our house in New

Jersey and bought forty acres of beautiful land at MacNab Ranch.

For three years at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas,

I didn't participate in the meditations or lectures very much. I had never

had a very good impression of the Buddhists in China. A majority were women

who blindly believed it was their fate to tolerate the intolerable so they

could gain a better life next time. Buddhism in China had become superstitious

and power-based. There is a  Chinese

saying: "The monks chant with their mouths but not their hearts." Since

I was reluctant to become involved, I thought, "I will just teach and do

my work." Chinese

saying: "The monks chant with their mouths but not their hearts." Since

I was reluctant to become involved, I thought, "I will just teach and do

my work."

Since I was teaching, I started to carve again.

I named my Buddhist carvings "still quiet light." When you have bright

light, you see clearly, and when you see clearly, you have peace. When

you are still, you can function and see better.

I designed two hands, coming together, for the doorknob

of the Buddha hall--a beautiful gesture of mutual love and respect; such

a great greeting to welcome each other by touching hands. Too bad the design

was not used. I also designed an entrance gate using this concept. The

Venerable Abbott Hsuan Hua had asked me to come up with a design for the

entrance, using certain criteria; it had to be Buddhist-related and something

never seen in the world, past or present. This was a tall order. I designed

two wedge-shaped stucco structures of abstracted hands that I felt would

go well with the surrounding stucco buildings. The traffic would come and

go through the palms of these hands and the Buddha eyes at the center of

the palms would serve as rooms for the gatekeeper. The Abbot liked the

idea, but others thought it was too far-out. However, I was happy, and

it did match the criteria!

Before I took leave from the University, I decided

to set up a contemporary Buddhist show, and told the Venerable Abbott that

I would organize the show by sending literature all over the world to request

entries. I thought the sangha should be the jurors. I was not too sure

myself what they would accept. He said, "Flory, all images are empty. They

are formed through each one's attachments. So what's the difference?" That

made a big gong go off in my head: "Wow! People form their own images,

but all are empty anyway. We think, 'This is good, this is bad; mine is

superior; yours is inferior.' This goes on and on, throughout the whole

world." That was a wonderful thing to learn.

In a piece called "Sojourner," I forgot myself and just started painting

with house paints on siding and six-by-sixes. Everyone is there. My dad

is there; many people I know are there in faces drawn or cast in cement,

placed inside and outside of three-dimensional boxes. Many mirrors were

included. This work is very hard to photograph, because it changes all

the time. People at the show would come and say, "I see Mozart." Others

said, "I see Beethoven."

My work is about the connection and interconnection

of all phenomena. Three-dimensional forms never look just one way, because

they are influenced by light and shadow. They show the forms, and also

have the ability to interfere with them. The black and white in my work

show this constant interplay, and the mirrors reflect and also create constant

change.

I recall a restatement of Buddhist and Taoist

doctrine about the all-embracing reality: "There is no difficulty about

the perfect way. Only we must avoid the making of discrimination. When

we are freed from hate and love, it will reveal itself as clearly as broad

daylight. Do not pursue the outer entanglements, nor dwell in the inner

void. Rest in peace in the oneness of things, and all barriers will vanish

without a trace. The more you strive to stop motion in order to obtain

rest, the more your rest becomes restlessness. As long as you are stuck

in dualism, how can you realize oneness? The object is an object for the

subject. The subject is the subject for the object. Know that the relativity

of the two rests ultimately on one emptiness."

People told the Dalai Lama that if he went

back to Tibet after twenty-some years, people wouldn't recognize him. What

do you think he said? He said, "If the Tibetan people have no need of a

Dalai Lama, then the Dalai Lama doesn't exist." He is so simple. He didn't

say, "Oh, how can this be possible? I am the living Buddha."

In reality nothing is purely black-and-white. Everything

is multi-layered and interactive. There is no bottom line. That is what

I am trying to express in my art. Where is the substance of reality, if

the same reality is so different to different people?

The beginning of my story and the end of my story

as an artist is about my bag of tools. At home in my studio I have so many

kinds of equipment and tools for welding, cutting, carving, modeling, grinding

and polishing. As a sculptor, I explore and learn, and in that process

I can never get away from construction. There is physics involved in working

with these materials--marble, clay, wood, styrofoam, stainless steel, bronze,

copper, ferro-cement and acrylic.

Most people see me as petite. They don't imagine

that I work with all these hard and heavy materials. I figure that if I

want something, then that is my price to pay. I have cut my hands and burnt

myself all over from welding. I still have scars from hitting my thumb

when carving marble.

The process of doing sculpture has created me. The

materials inspire me and work with me. I have to deal with them, fumble

with them and have patience. Things never go as you dictate. With carving,

you progress chip by chip--slowly. You have to respect the materials. Nothing

meaningful is done overnight.

The feeling for the solitary lifestyle was

deeply imbedded in me. My studio, which is deep in the mountains, is a

place where no visitors come--only the meter reader, the birds and deer.

I love the solitude.

|

This sculpture of marble laminated with stainless steel was commissioned for one of the most beautiful and costly buildings in Taiwan — with very

expansive green glass and a Spanish-tile facade. The building needed a

very strong sculptural form, and the architect suggested it be two stories

high. |

|

Where is the substance of reality, if the same reality is so different

to different people?

My work is about the connection and interconnection

of all phenomena. |

I have done quite a few commissioned works in both Asia and the US.

My work in Taiwan is very new. The people there are still traditional in

their views.

My work in China is a road back home for me.

I have been invited to do a show of my recent work in Beijing and have

worked on a golf course in Xiamen, China--a port city on the coast in the

semi-tropical region of the Guangdong Province. That area used to be under

Portuguese rule, and there are many beautiful Portuguese buildings there.

I have worked on golf courses both in Taiwan and Xiamen for two and a half

years. These gathering places gave me a chance to learn.

I have always admired the non-compromising conscientiousness

of Japanese workers. In 1991, I was honored to be invited again to participate

in an international sculpture symposium, held in Kikuchi, Japan. At the

end of the symposium, all our sculptures were to be set up in the sculpture

garden. Local masons helped to cast the bases. Before drilling the holes

to anchor my sculpture,

they cleaned the surface first, then sharpened their pencil to a clear

point before marking with it. Then they started to drill --first with the

smallest bit, then a bigger one. Two people guided the horizontal and vertical

directions. It was hard for any of us to find any imperfections.

Unfortunately, the workers in China and Taiwan were

not as concerned with quality as the Japanese. That made creating large

commissions there difficult and completely exhausting. On the other hand,

my work as an art consultant for golf courses has enlarged my scope as

a sculptor. Landscape design is such a joy. Nature is "never twice the

same." I have designed golf-course entrances, placed huge boulders around

lakes, decorated clubhouses for New Year and Christmas celebrations, installed

a carved marble piece that I made long ago in Cararra, and also created

an installation of pieces carved by other sculptors.

For years I had not been able to write my side of the story to my children

about what happened before, during and after my divorce. The relentless

bombing of Kosovo by NATO angered me so much that I was motivated to do

something. The arrogance of the war and my ex-husband's arrogance both

enraged me. How could John be so cruel to his vulnerable children, that

he would denounce their mother and tell horrible tales of me abandoning

them? I realized that some people justify their cruelty to others by simply

demonizing them.

I had kept my silence for years, mainly for

three reasons. First, I still harbored the pain of betrayal, and felt shame

to have subjugated myself to John's power and demands. I finally realized

fully that we did this to each other. I was part of the cause of what happened

to my family. Second, it was against my nature to do to others what I do

not admire. I don't talk behind people's backs. For a long time, I had

felt reluctant to speak about the past or to write about it, even to my

children.

Third, I felt that when parents fight with each

other, children suffer the most. Since John and Anna had brought the children

up, they had earned credit; for me to speak about the past might alienate

the children from them.

I have since learned how important and necessary

it is for children to know the story from another side. Through understanding,

maturity and compassion, they might be able to resolve their deep pain

and questions; then we can all be on our way to healing.

I wrote for two weeks, night and day, and

could not sleep. All that anger and deep imbedded pain surged up, but I

knew that to write with anger and resentment wouldn't solve any problems.

It would only create more confusion. Finally I decided to use the format

of a journal. I wrote a narrative description of the time, place and events

without commentary. This was all written from my personal experience, with

no criticism, no innuendo, no attacks, no blame--a straight journal from

the point of view of the one who went through it. I wrote for two weeks, night and day, and

could not sleep. All that anger and deep imbedded pain surged up, but I

knew that to write with anger and resentment wouldn't solve any problems.

It would only create more confusion. Finally I decided to use the format

of a journal. I wrote a narrative description of the time, place and events

without commentary. This was all written from my personal experience, with

no criticism, no innuendo, no attacks, no blame--a straight journal from

the point of view of the one who went through it.

My daughter asked me not to send the letter

to her dad and Anna, for fear it would create a hell for all if I did.

Since I chiefly wanted to relieve doubts and answer questions for my children,

I agreed to send the letter to them only.

It mattered to me so much that it took years

to feel right in my heart about writing it. I wanted to help my children

to forgive, and also to appreciate what they had been given so they could

embark on their own road to healing. Afterwards, I felt the pure light

of relief. It has made me feel so much closer to them to recall our happy

years together with so much laughter and joy. I had buried those memories

along with the pain.

Whether this benefits the children or not, they still have to walk their

own road to discovery and to recovery. I have walked this road all these

years just to understand and resolve many questions. Now, they have to

do this for themselves.

|

I was born in mainland China and moved to Taiwan when I was thirteen years

old, then to the United States after high sdad

was an official in the Chinese government, but also a writer and a scholar.

He surrounded me with books. Since I was nurtured that way, I also wanted

to be a writer.

I was born in mainland China and moved to Taiwan when I was thirteen years

old, then to the United States after high sdad

was an official in the Chinese government, but also a writer and a scholar.

He surrounded me with books. Since I was nurtured that way, I also wanted

to be a writer.

they cleaned the surface first, then sharpened their pencil to a clear

point before marking with it. Then they started to drill --first with the

smallest bit, then a bigger one. Two people guided the horizontal and vertical

directions. It was hard for any of us to find any imperfections.

they cleaned the surface first, then sharpened their pencil to a clear

point before marking with it. Then they started to drill --first with the

smallest bit, then a bigger one. Two people guided the horizontal and vertical

directions. It was hard for any of us to find any imperfections.