|

|

|

|

When I was nineteen years old, I began to study basket

making with Elsie Allen. That was thirty-three years ago. I studied with

her for several years--starting with a basket class and then at her house.

I also learned by sitting and talking with her and with Annie Lake. I used

to attach myself to the elder women of the tribes around the valley--where

I felt the knowledge was. Later I became wild and didn't study with them

again for a long time.

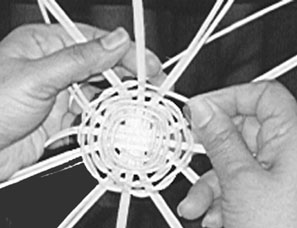

I have been doing baby baskets from the beginning. Every one is different. When I started, I used to think about them all the time. I fell in love with them, and then I had to let them go. It was like pulling them out of my arms.  Now I am getting more into coil baskets. They take more time to learn.

You need patience to pick and clean the root, and to do many things in

preparation. My husband Rick collects materials for me. He went to the

coast to take a picture of a bark house the other day and stopped along

the road and gathered sedge basket root. When he brings it home I split

it and dry it for making coil baskets. All this takes time. Sedge is also

called blade grass because it is so sharp that if you pull it wrong it

will cut your hand.

Now I am getting more into coil baskets. They take more time to learn.

You need patience to pick and clean the root, and to do many things in

preparation. My husband Rick collects materials for me. He went to the

coast to take a picture of a bark house the other day and stopped along

the road and gathered sedge basket root. When he brings it home I split

it and dry it for making coil baskets. All this takes time. Sedge is also

called blade grass because it is so sharp that if you pull it wrong it

will cut your hand.

I am a member of California Indian Basket Weavers, who have special conferences and a publication that recently did a profile on me for spring. I sold a basket to the Smithsonian last fall when they sent an anthropologist to the Sun House for the Pomo basket exhibit that was here. They saw my Lake County baby basket in the gift shop and purchased it for their own collection. I also gave them a Mendocino County baby basket (same materials--different design) to go with it. These two baskets completed their collection of California Indian cradles, and are now among the baskets in an exhibit that is loaned by the Smithsonian to other museums for educational purposes. The Yokayo Rancheria--the place where I live and was pretty much raised--has been here since 1886. I have a pretty traumatic history behind me. In 1990 my nineteen-year-old son was murdered at a drunken teenage party 150 yards from my house. After that I picked up basket making again. It kept me sane and on the right road, so I wouldn't feel like killing that person who killed him. I can laugh about it now, because I am getting stronger. As time goes on, my basket designs will show more of what I am inside. The designs on baskets I see belong to the person who made them. I don't want to copy these; I want to come up with my own. I work on the baskets every day. I have four children between twenty-three and thirty-three years old, and a son who's eleven who lives at home. I have taught him basket making. He is also a singer and a bear dancer. Cynthia Daniels from Hopland is teaching a Pomo language class for him and the other dancers. She took classes from a linguist in Berkeley, but she knew the language pretty well because her mother, Kay Daniels, spoke it. In order for the Native American people to survive all the changes that go with the millennium, we need to hang on to some things from the past and remember how it used to be, and also recognize how good we have it now. By combining both, we can be a stronger people. I think the baskets, the dancing, the songs, and the language complete the circle.

I don't want to leave this earth having done nothing. I felt like, "There has to be something I can do to put a mark on this world." Doing baskets helps me bring out the spirituality that I keep inside me. I do baskets because I feel chosen. They also let me make a connection with kids. I teach basket making at Coyote Valley Reservation, at the public elementary schools, in clean and sober classes for at-risk kids in high school and junior high, and in ethnic and teacher training classes at the college. We use contemporary material--ratan--for twining because it is easy for people to work with. If Native American kids look like they are willing and interested, I'll teach them to use the traditional materials that we collect and gather from around the county. My husband Rick and I are keeping on the red road of being alcohol-and drug-free, and talk about this as we teach basket classes--especially to Native American kids. When you relate to kids on their own level, they understand. We don't get into their life history, but we do talk about behavior. Baskets are a good tool for talking about the ancestors and how they lived. We try not to have bad thoughts or feelings and to stay positive when we are making them. We tell the girls that we don't make baskets when we are on our moon. I meditate and think about the good things we have to work with. The ancestors didn't have so much, yet they were able to make these beautiful baskets. My father always said that we have to go along with the world: "The world is moving and we have to move right with it." We have to integrate what we believe into what is happening in the world today. We can't stay back in the past. We have to bring it forward. There will be changes, but we try to keep certain traditions alive and abide by them. |

| Anna

Marie Stenberg ~ The Core of Being ~ Cover Artist:

Beva Farmer From the Editors ~ Forest Activists: Personal Stories (Introduction) In Those Days ~ Julia Butterfly ~ Spirit for Survival The Way of the Basket ~ Zia Cattalini |

Copyright © 1999 Sojourn Magazine.(All Rights Reserved) |