I'm really lucky to have had a great dad who loved me

as a child and loved to hike in nature. When I could, I would walk with

him. He was always pointing out beauty to me--a little puddle of water with

sparkly pebbles shining from the inside, or maybe a leaf with beautiful

patterns. My mom was always busy re-creating her nest to adapt to her growing

family. She was probably the only woman in our town to own and use a power

drill and saw. When I was eight years old she added an upper level of three

bedrooms and a bath to our home.

I moved to Mendocino in 1972. Several years later I began

caretaking my aunt's abandoned property in Little River. The land I lived

on is adjacent to what's now called the Enchanted Meadow, just above the

Albion River's north side. It was there that I dug in deep with myself--in

a little shell of a cabin surrounded by forest and pygmy prairie with huckleberries.

I lived with no running water, no electricity. There weren't many 20th

century distractions around to diffuse the teachings of nature. The wind

through the trees taught me many things. This was a very peaceful existence.

My first child, Alia, was born on the land, birthed in a tipi in May of

1980. In November of 1992, my second daughter, T'ocha, died on the land

in utero at 9 1/2 months while Louisiana Pacific was suing me for trespass.

In 1987, when LP wanted access so they could plow a road

into Enchanted Meadow forests, they met with neighbors. That was when I

gave notice; I used the area often. It was sacred to me. They never cited

me for trespassing, but sued me for it over five years later. In 1989 I

heard that this area was going to be logged, and that one of the harvest

plans had already been approved and another was about to be approved in

two days. I learned that, although we could write letters to the California

Department of Forestry (CDF), they wouldn't stop the cut. I wasn't eager

to deal with any bureaucracy or "good old boys," but I knew I had the passion

and the will to use my power to keep that place from being logged. That

realization was affirmed throughout my being the moment I heard this cherished

spot was endangered.

I called up CDF and Louisiana Pacific and

told them that it was a beautiful sanctuary and that it should remain that

way. They told me there was nothing anyone could do. I said, "There's really

nothing I can do?" The guy on the phone at CDF said, "Well, you could sue

us." I said, "Okay, if that's what I have to do, I'll sue you." That was

the end of that conversation. I started networking and a lawsuit was filed

two weeks later.

The place wasn't always called Enchanted Meadow. In our Little River

neighborhood it was just called "The Meadow." On the south side of Albion

River they called it "Loren McDonald's Cow Patch." A forest activist and

friend, Richard Gienger, advised me not to use the generic reference numbers

that the timber companies place on forest lands they intend to log, like

Timber Harvest Plan (THP) 1-89-100. He suggested we identify the

THPs by their local names, or name them ourselves. He said that in the

Sinkyone, a stand of redwood trees was named Sally Bell Grove after a Pomo

woman. I came up with the name Enchanted Meadow, a broad term for beauty

and magic. After a long hike through the forest, you find yourself suddenly

drenched in sunlight in lush velvet green environment--blue herons, the

changing tides--truly a magical place. Other places in this area have been

named as well: Raven's Call, Bear Claw Ridge and Bobcat Bend.

My relationship to this place--to the water,

the air, the sun, the earth, the animals--is what gave me the strength and

credibility to take on this enormous task. When I hike down to the bottom

of Enchanted Meadow, I make a call. I've done it for twenty years. The

animals--who can smell me--probably think, "Zia, you don't have to make that

corny call. We hear you, we smell you, we know it's you."

When the lawsuit was filed, I didn't dwell on what the repercussions

might be. My decision came straight from the heart. The trees, a most vulnerable

species, can't run off to find safety--they remain rooted in the earth.

They need allies here. Once I decided to do it everything started falling

into place.

We filed on three THPs: two at Enchanted Meadow

and one at Kaisen Gulch. Even though the THPs were rubber stamped and therefore

"legal," they were still immoral. In this nestled pristine spot, between

two communities, LP had neither the vision nor the understanding to recognize

that the value of the land in its natural state was worth more than money.

My friend and neighbor, Virginia Sharkey,

worked with me the first year. We shared a mutual love for the meadow.

I called the Mendocino Environmental Center (MEC) which was budding as

the nerve center for environmental action in the county. This was 1989.

Betty and Gary Ball were there eager to assist. Betty and I often talked

on the phone. She gave me phone numbers and helped orchestrate things.

The biggest chores were getting an attorney, paying the attorney and informing

the community. We've had many attorneys since, and four lawsuits and three

appeals. When in court for the first time, I felt tremendous joy. I remember

thinking, "This feels great! We've worked, paid our attorney and now she's

defending the trees!" Our lawsuits have always succeeded at some point

in court. We'd take the money we were reimbursed and put it back into legal

fees for the next lawsuit.

From 1989 to 1992, I worked hard to keep the issue

alive. We won on the Kaisen Gulch plan in the appeals court but lost on

the Enchanted Meadow plans. Then, when LP was going to log, there was a

lot of interest that had already been generated. We filed a second lawsuit

in the spring of 1992 because the old logging plans didn't comply with

new forestry regulations. The judge ruled against us. We eventually got

CDF to issue a stop order. Then LP sued CDF, me personally, and the Friends

of Enchanted Meadow. Judge Luther overruled the CDF stop order, allowing

LP to cut. This galvanized many people in the community to support us,

hundreds of people came, and it really was a big event. The magnitude of

the support for the forestland was overwhelming. The protests and logging

lasted for six weeks until an injunction was ordered by the appeals court

against all logging pending a decision. This historical six weeks of protests,

rallies, courage and song is known as the Albion Uprising. When it became

a media event the energy changed. In came people not connected to the land

but who wanted in on the action. At this point, it felt like the land was

a big red steak and the different factions were dogs tugging and snarling

-- fighting each other for a piece of it. I was only able to take a breath

when the case went to appeals court and sat dormant.

The first fundraiser I did was to send a Native American woman, Margeen

McGee to Washington, D.C., to run for Congress. Corn is the native grain

of America, so we sold popcorn at the Fourth of July parade in Mendocino.

The following year we popped 1000 bags of popcorn to pay for legal fees

for Enchanted Meadow. After that, the Albion Headlands group did

the popcorn at the parade; it's become a tradition. Since the beginning,

it's been fundraiser after fundraiser. We did everything we could think

of. For months my daughter Alia went around the village of Mendocino

and talked up the tourists. She wrote this little story about Enchanted

Meadow and sold buttons she made. My two friends, "the Duke and Duchess

of Oil," hoofed the pavements getting donations, and the poet, ruth weiss,

collected donations. The Albion community was fantastic in their support,

and the tourists were generous. We contacted experts, mapped, photographed,

and documented habitat conditions, measured trees, found out where all

the old growth was, etc. We became far more familiar with the land than

the "owners."

Louisiana Pacific tried to squelch the uprising by suing all the protesters

(about 100) they could identify in one broad swoop using a S.L.A.P.P. suit

("strategic lawsuit against public participation"). All were charged with

the same thing--trespass and conspiracy to interfere with economic relations.

Offenses were named as tree-sitting, playing cat and mouse, trespassing,

yarning or spiderwebbing (you can't cut string with a chainsaw), and yelling

at loggers. LP's relief was to keep us off the THPs--about 290 acres--and

charge punitive damages. What on paper read as a silly action had far-reaching

implications. Those who owned homes could actually lose them. LP's attorney

went overboard in her vigilance to prosecute us. Most defendants settled

out with LP earlier rather than later, with injunctions expanded to thousands

of acres and stipulations that inhibit not only their actions but those

of their associates in the future.

The legal documents I received were about the size of

a cord of wood. It became a living nightmare, a demon devoted to my persecution.

My legal representation was inconsistent. I became a victim; my grief and

torment were horrible. My baby was big in my belly, my father had just

died, the trees were falling, and people were out there risking their lives.

I was plagued with guilt and concern.

While the S.L.A.P.P. suit was ongoing, the

state changed the forest practice rules to require cumulative effects assessment.

LP tried to satisfy this rule using a minor amendment, meaning no public

comment. We sued on that issue, which resulted in an important ruling on

the rights of the public in the timber harvest plan review process. They

were required to file it as a major amendment. But when they did, they

left out a lot of information that the public should have had. The Redwood

Coast Watersheds Alliance sued them for that (and other matters) last year.

This latest lawsuit hasn't gone to trial yet.

LP sued me for trespassing and conspiracy in a S.L.A.P.P. suit in April

1992. In February of 1997, I entered into a settlement agreement with LP.

If I agreed not to sue them for malicious prosecution or maintaining a

frivolous lawsuit against me, they, in turn, would deed over the Raven's

Call Forestlands to Friends of Enchanted Meadow. They also agreed to sell

me a riparian corridor of about ten acres.

It's been two years now. LP is gone. The new

owners--the Fisher family of The Gap--call their LP purchase "The Mendocino

Redwood Company (MRC). So far, the delay in my land transfer settlement

is due to zoning complications. MRC inherited the responsibility of my

settlement but wants to log up to the Raven's Call Sanctuary, leaving no

protective buffer to this home of spotted owl, blue heron, raven, osprey

and threatening a stream perfect for coho salmon rehabilitation.

Through all these years of activism--trying

to save this forest--I've supported myself and my daughter, kept my shop

going, kept my life going. It's been very difficult. The work I've been

doing has been very unpopular in many ways. There is not a lot of real

solidarity here on the coast with forest issues because we're dealing with

an economy based on logging, even though it's dwindling, and we're dealing

with private property rights. But we're living in a time when people have

to realize that we simply can't do anything we want on "our" land, because

it's not really "our" land; it belongs to the Earth.

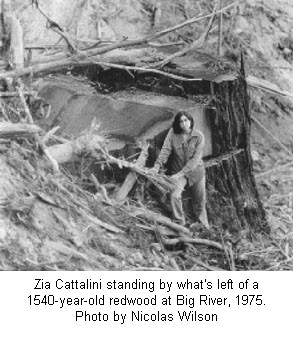

Zia Cattalini, a native Californian, is the founder of the Friends

of Enchanted Meadow and board member of the Redwood Coast Watershed Alliance.

She has been a forest activist since 1989 and has been instrumental in

demonstrating that anyone who cares and is committed can make a difference

in environmental policy. Zia is a textile artist and fashion designer

with a shop in Mendocino called Zia's, where she sells her one-of-a-kind

designs.