I

started drawing when I was really young and later showed a facility for

capturing gestures with a Rapidograph drafting pen. When I was a

senior in high school, I went to the local art academy in the afternoons

to take life-drawing classes. After that, I had to make a decision whether

to attend art school or college. I was accepted at Cooper Union, a free

art school in New York, but there was no housing there. I was just a girl

from Cincinnati--unprepared to be on my own in New York--so I went to Sarah

Lawrence College instead. I didn't do much art, but did spend my junior

year at Columbia University, living in Harlem and attending a life-drawing

class at Columbia General Studies. This was my most meaningful art experience

since high school. I graduated in 1963, and went on to graduate school

in Cincinnati to become a community planner.

I still have drawings from when I was

in college and thereafter. My art is what I see. I have always found the

external world endlessly stimulating; in New York and later in my travels

I carried a sketchbook everywhere. It wasn't so much a discipline as that

I had to keep drawing. I would see the faces of people, and I would have

to capture them.

My master's degree allowed me to have many

rich experiences and to work in other countries. In 1968 I went to London

where I attended the London School of Economics for a year. Student demonstrations

were going on at that time all over Europe. When the students in Paris

were protesting the government of Charles De Gaulle, I flew to Paris without

knowing French, and spent an adventurous and amazing week there.

London was also having demonstrations against

the Vietnam War. At a student demonstration, I noticed an elderly artist

drawing in the huge school auditorium. I recognized his drawing style and

asked him whether he could possibly be Felix Topolski. (My mom, a librarian,

liked his art when I was young, and we had collected his books.) He was.

He invited me to come to his studio and bring some of my work. He told

me to dare--to be as daring as I possibly could. If there was something

I wanted to do, he said, I should do it.

Shortly

after that, the school year was coming to an end. At a party somebody handed

me a flyer about flights to Africa. I had been in a course with students

from all over the Third World who gave talks about their country, and when

the students from Zambia spoke I was drawn to this place in Africa. I decided

to go there, but Zambia turned out to be the one place in Africa I never

visited. I ended up booking a one-way ticket to Nairobi, Kenya without

even knowing which side of the continent it was on.

Shortly

after that, the school year was coming to an end. At a party somebody handed

me a flyer about flights to Africa. I had been in a course with students

from all over the Third World who gave talks about their country, and when

the students from Zambia spoke I was drawn to this place in Africa. I decided

to go there, but Zambia turned out to be the one place in Africa I never

visited. I ended up booking a one-way ticket to Nairobi, Kenya without

even knowing which side of the continent it was on.

On the airplane, I sat next to an English

anthropologist who was studying a bush tribe in Tanzania. He had the photographs

from his fieldwork. As we were talking, I suddenly became so overwhelmed

by the realization that I was going to Africa all by myself without any

idea of what I would do when I got there that I burst into tears. The Englishman,

being polite, went back to reading his papers, and when I finished crying

he brought out his photographs and started talking to me again.

The plane landed in Cairo for a three-hour

stopover. Some Egyptians came to the airport and asked if anyone wanted

to pay an English pound to go see the pyramids. It was about 2 a.m. We

got into taxis and started riding through Cairo. Even though it was the

middle of the night, Cairo was really hopping. Men dressed in long, flowing

robes pushed huge carts of watermelons. The road to the pyramids passed

all the embassies on a wide avenue. Six or seven taxis raced each other

and honked their horns. It was a full-moon night. When we got to the pyramids

I decided that I liked Africa, and that everything was going to be okay.

I could stop crying. And so I loved Africa from the beginning.

I worked in different planning jobs in Africa.

I met an Episcopal priest in the cathedral in Nairobi. His friend, a city

planner, was leaving her job and asked me if I wanted it. The boss asked

me what I wanted to do. I said that I like to work with people, and he

said, "Good, none of the rest of us really do. We are all engineers. We'll

give you all the people stuff." I worked in the squatter areas of Nairobi,

where the illegal housing was. I was a crusader for years, trying to get

homes legalized. We got money from a World Bank project.

When I left Africa, I went to various parts of Asia for six months, I was

planning to go back to America after that. Then a group of friends I had

met in India turned up in Bali, and introduced me to some people who were

planning to sail to Africa. I thought I would like to go sailing, and I

was missing Africa, so when they told me about a man named Martin who was

looking for someone to sail with him, I went to the port where he was painting

his boat. He was very English. I later found out that when he saw me dressed

in a yellow outfit --one I had acquired in India--with a long scarf wound

around my long wild hair, he thought, "No, not her." We did take off and

sail to Africa together, and eventually we got married.

When I left Africa, I went to various parts of Asia for six months, I was

planning to go back to America after that. Then a group of friends I had

met in India turned up in Bali, and introduced me to some people who were

planning to sail to Africa. I thought I would like to go sailing, and I

was missing Africa, so when they told me about a man named Martin who was

looking for someone to sail with him, I went to the port where he was painting

his boat. He was very English. I later found out that when he saw me dressed

in a yellow outfit --one I had acquired in India--with a long scarf wound

around my long wild hair, he thought, "No, not her." We did take off and

sail to Africa together, and eventually we got married.

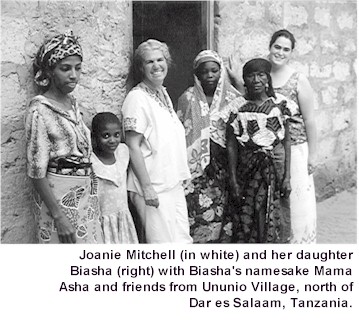

When I returned to Africa with Martin, we

lived in a fishing village north of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. I worked for

the Ministry of Planning and Physical Development. Again I worked with

squatters. Since Martin and I had no children, people felt sorry for us

and they begged Allah to pity me and give me a baby. I promised Mama Asha,

the woman who more or less adopted me in Ununio Village, that if ever I

had a child, I would name her Asha. Later, when we had our daughter, we

did name her for Asha. Later on, our son Daudi was also named after a friend

from Africa.

It was wonderful to live in Africa in the

late 1960s and early 1970s, soon after the arrival of political independence.

No one had ever heard of AIDS, and the great famines of the 80's were yet

to come. People were hopeful about development then. The countryside (the

"bush" we called it) was wonderful--full of animals, and of wise and humorous

people who won my heart.

In 1975 I returned to America after nine years

away. The Africans in my village had advised me to get a home in the country

to which I might always return. This was their custom. In 1984 Martin and

I bought land with our communal family, the Hog Farm. We live at the Black

Oak Ranch in Laytonville. This is where Camp Winnarainbow happens every

summer, and every Labor Day, we have our music festival--the Pignic.

Right after I moved to the ranch, I started

a shop, Nobody's Business. Martin and I enjoyed traveling with our children,

and one year when we drove down to Guatemala, camping all the way through

Mexico, I bought a few things for Nobody's Business. That's how I started

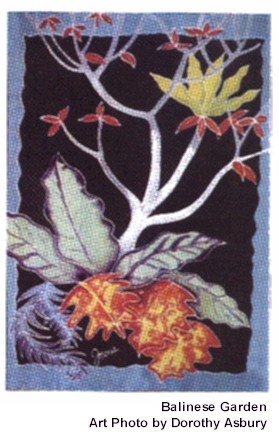

becoming an importer. About six years ago, I went to Bali again to buy

clothes. My balinese friend named Made introduced me to her college friend,

Chendra who was a tailor. Chendra was so clever that I could bring her

a picture and ask her to make a dress from it. We bought fabrics at local

shops and made clothes which I brought back to my store.

When

I first saw batik, I was staying in a guesthouse in Bali. The family who

owned the guesthouse did batik too. I said to myself, "This is drawing.

It's drawing in wax. I want to learn how to do it." I asked them if I could

work on the batik piece that the whole family was painting together with

sponges tied onto sticks. Once they handed me a sponge and I started applying

the dye, I knew this was something I wanted to learn more about.

When

I first saw batik, I was staying in a guesthouse in Bali. The family who

owned the guesthouse did batik too. I said to myself, "This is drawing.

It's drawing in wax. I want to learn how to do it." I asked them if I could

work on the batik piece that the whole family was painting together with

sponges tied onto sticks. Once they handed me a sponge and I started applying

the dye, I knew this was something I wanted to learn more about.

I studied in Java, which is the world center

of batik--particularly picture batik. You draw with a tool called a tjanting

which is a little cup with a handle and spout. You dip the tjanting into

hot melted wax and the wax flows out of the spout to make designs on the

cloth. The cloth is then painted with dye which colors it everywhere except

where the wax makes it resist the dye.

I studied with a wonderful, charming

and articulate man named Tyias. On my next trip to Java I planned to study

with him again, but by accident I met my other teacher, Umar Hussadin.

I was travelling in the Javanese city of Solo, a city of thousands of batik

makers. On a bicycle tour of Solo, I was introduced to a very poor man

who made batiks in his house. This was Umar. He offered to teach me, so

I left the bicycle tour and stayed there to study with him.

The people who taught me batik were very patient. At first I would drip

wax all over, and then would have to remove my mistakes. Umar taught me

how to work large. We worked on sarongs which are two-meter pieces of fabric

that people wear as wrap arounds and find many other uses for. In India

they call them lungis, and in Africa they are called kangas.

In Umar's village, the people made both hand-drawn and metal-stamp batik

sarongs with repeat-pattern designs. Umar's village produced 2,000 sarongs

a week. They were shipped to Bali and then to other countries such as South

Africa, Brazil, Japan and the United States. The work was contracted through

a middleman. Umar's brother-in-law helped a big contractor. Umar's whole

house was piled up with fabrics and stamps. The kids worked too. Everybody

worked.

The people who taught me batik were very patient. At first I would drip

wax all over, and then would have to remove my mistakes. Umar taught me

how to work large. We worked on sarongs which are two-meter pieces of fabric

that people wear as wrap arounds and find many other uses for. In India

they call them lungis, and in Africa they are called kangas.

In Umar's village, the people made both hand-drawn and metal-stamp batik

sarongs with repeat-pattern designs. Umar's village produced 2,000 sarongs

a week. They were shipped to Bali and then to other countries such as South

Africa, Brazil, Japan and the United States. The work was contracted through

a middleman. Umar's brother-in-law helped a big contractor. Umar's whole

house was piled up with fabrics and stamps. The kids worked too. Everybody

worked.

The batik industry is incredibly competitive

right now, especially since the recent crash of the economy and the devaluation

of currency in Indonesia. As batik became popular all over the world and

as more people got into the business, rich people started factories and

hired workers. Now the price of the fabric is going up, and the quality

is going down. Poor people cannot make their own batik business, because

they don't have enough capital to buy the white fabric, stamps, dyes and

fixative. Therefore, a middleman comes in with the contracts, makes an

order and finances the business. Orders up to 15,000 pieces are done by

the people in the villages. The men stamp or make wax drawings with the

tjanting, and the women stretch the cloth out on simple wooden frames

and paint the fabric. Then they boil the wax out in a forty-four gallon

drum, take it to the river and wash it out.

The environmental aspect of this process is appalling. Caustic soda

is added to the fixative. Bleaches are also used. Bali has some environmental

regulations, but basically it is a mess. I used to sit on the edge of the

river in Solo and watch, but I didn't feel I could say anything because

what in the world are they going to do? They don't have the money to change

the situation. The people live a very simple life. One well and one outhouse

was shared by many families.

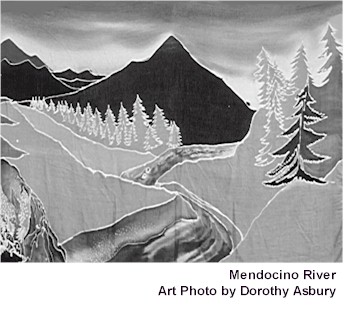

As I learned batik, I became less interested in buying and selling things

and realized that I really wanted to do my own batik designs. I turned

my attention to art, both my own and that of the other artists of my community.

This year Nobody's Business moved 1/2 mile north of Laytonville, right

out there on highway 101. Half the store is now an artists' cooperative

called the Mendocino Art Shop. "Art shop" is a term used in Bali and Thailand

that refers to the tradition where the artist produces and sells her art

in the same place. I hang the batiks out by the highway, and people stop

because they are attracted by what they see.

As I learned batik, I became less interested in buying and selling things

and realized that I really wanted to do my own batik designs. I turned

my attention to art, both my own and that of the other artists of my community.

This year Nobody's Business moved 1/2 mile north of Laytonville, right

out there on highway 101. Half the store is now an artists' cooperative

called the Mendocino Art Shop. "Art shop" is a term used in Bali and Thailand

that refers to the tradition where the artist produces and sells her art

in the same place. I hang the batiks out by the highway, and people stop

because they are attracted by what they see.

As soon as the weather is good enough I work outside

with my friend Sheila--doing everything the way I learned it in Java.

I still go back to Bali periodically to work with Umar and with another

batik artist, Ketut. I stay for as long as two months.

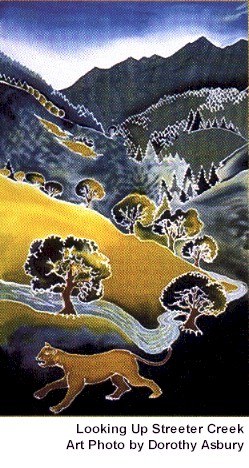

I have been doing batiks of tropical flowers,

tropical scenes, scenes of the Eel River and landscapes of Mendocino

County--oak and madrone trees, the folds of the hills, the structure of

the land itself and the way the rivers go. This is our land here. I work

with themes, sometimes making many pieces on one subject--such as patterns

of the night sky, chili peppers or butterflies.

My store went from a junk store to an import store to a business that

promotes art and the creation of art. During the time Nobody's was primarily

an import store, I got involved with the fair trade movement and became

more and more concerned with the conditions under which things were made.

I learned a lot about this, and shared my stories with customers.

The intention of the fair trade movement is good. We all need to know

a lot more about how our clothing is made, for instance, and its impact

on the Earth. A thirty-dollar dress didn't just cost thirty dollars. There

is an environmental cost too. I have done my share of talking to people

about the origin of the clothing and art objects I sell. When I tell the

shoppers about the artists, this establishes a connection with them. I'm

also very happy to know that my artist friends get money directly from

my hands to theirs.

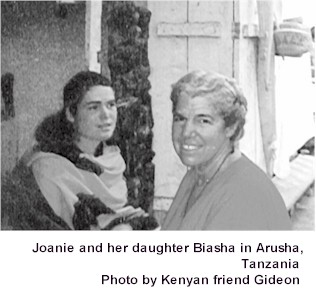

This year I made two important returnings. I took my children to see

Africa--which they came to love as I do--and to make a pilgrimage to meet

their namesakes, Mama Asha and Mzee Daudi. I also undertook a community-planning

project in my own town of Laytonville. The U.S. Forest Service gave a grant

to the Laytonville Municipal Advisory Council (MAC) for preparing a community

action plan for Laytonville. I coordinated a survey as the first step in

the planning process.

I really enjoyed doing this community survey.

I have done a lot of research--but never of and for a whole town. I worked

with several community teams, a committee of extraordinary women from the

MAC and a team of volunteer interviewers. The nineteen people on the interview

team came from different parts of our diverse area. They all worked on

the survey because they care about our community and wanted to give people

an opportunity to express themselves about the issues facing us all. In

the process, we learned a lot about our community. We learned about the

people's wisdom and how much most people appreciate living here. They also

understand the fragility of the things they value, the natural environment

and the "small town" way of life.

Although I have loved going back to

community development work--the work that had been so satisfying in Africa--now

I am thinking of returning to Bali to work with Umar and Ketut. I am dreaming

about doing batik all day, every day. I feel batik calling to me.