My mother enjoyed singing and taught the songs to my sister and me when we traveled with her in the car. One song in particular, Mountain Song, was a favorite. When my father re-enlisted in the Navy, his ship would pull into port in Long Beach or San Diego and he would travel by bus to Flagstaff, Arizona to meet and spend a few days with us. My mother, sister and I drove from where we lived near Gallup, New Mexico and as we came close to Flagstaff, we could see the sacred mountain San Francisco Peak. We would acknowledge its beauty by singing Mountain Song. We were excited to see our father and sang with excitement. After the visit, we sang the song again while driving home—this time with less enthusiasm as we watched the sacred mountain appear smaller and smaller. Our song let her know we would return. Singing was good. It helped keep my mother from crying on the way home. Memories of those weekends are filled with much happiness. I felt the love my parents had for one another and used to wish hard for my family to be together all of the time. THE MOVE TO CALIFORNIA

|

||||||||

|

|

|

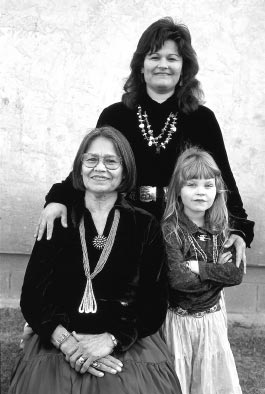

Sharon

Burch

Photo provided by Canyon Records, Phoenix, Arizona |

Then I satisfied my love of music by taking

a beginning guitar class. I remember sitting in my closet

wearing a sombrero hat—playing and singing quietly to

myself. The hat allowed me to hear myself better but blocked

my voice from traveling outside the closet. I enjoyed singing

and didn’t care what my voice sounded like to myself.

It felt good. I remember sitting in class waiting for school

to end so I could go home to my closet. I still didn’t

feel comfortable singing out loud, even in front of my family.

During this time, my mother gave birth to my youngest sister,

Sheila. My father was out to sea more and more, and my mother

seemed preoccupied with my two youngest sisters. This was

a difficult time for all of us. I wished we could move back

home to my grandfather’s place in New Mexico.

After high school, I returned to the reservation to attend

the Navajo Community College in Tsaile, Arizona. That was

an exciting time. A couple of months into the school year,

there was news that the college was hosting a folk festival.

My college roommate suggested I perform because she had heard

me sing and play my guitar softly a few times. I knew I wasn’t

ready, but she finally persuaded me. Since she also liked

to sing, I asked her to accompanying me on stage. We sang

a simple folk song and our performance went so well that I

wanted to try again. My roommate moved on, so the next time

I went on stage, I went alone. I was nervous but took on the

challenge of a solo venture. My performance was a disaster.

I forgot the words to the songs, forgot the correct chords,

my voice cracked and I felt very disoriented and embarrassed.

But still, something strong was pulling me, wanting me to

continue.

Now, after years of performing, I still get nervous, but I

am more comfortable on stage. I think it’s good to feel

a little nervous; it adds electricity to the performance.

I don’t put much time into practicing guitar or singing

because I don’t want to lose my enthusiasm or spontaneity

in my performance. I never know what the outcome will be.

I don’t like to perfect a song and always leave room

for improvisation. However, I do review the songs to see which

ones capture my heart and attention. I don’t want my

singing to become mechanical and formulaic, so I wait for

the moment that feels right to me. That’s probably why

I’ve made only four albums in the past twenty years.

This doesn’t mean I’m not enthusiastic. I have so

much passion about my songs. They are very sacred to me. They

are a way of life for me, and I want to share them with people.

I don’t listen to my recordings much but sometimes, when

my songs unexpectedly come out to greet me, we become friends

again.

The Colors of my Heart album came out last year. Its songs

are written for people of all ages, but many have special

messages for children. For example, We Are Here expresses

the need to take care of ourselves, to love one another, to

be with our surroundings and to just be. Another song called

Don’t Be Afraid tells how nature makes her music during

thunder and rainstorms. Little Starshine is a song I wrote

about my first baby. It says, “deliciously may you sleep,

deliciously may you dream, my sweet little girl.” I use

the Navaho words that most express my feelings.

I have received a lot of support from my family and friends

to do this music and would not have done any of it if my grandfather

had not given me his blessing. Before recording my first album,

my mother and I asked my grandfather if it was okay to sing

about the Blessingway using our Navajo language. He said yes,

that it would be all right but that I should sing my songs

with great reverence. He gave me his blessing. This meant

so much to me and has given me the strength to continue and

not feel bad when critics analyze my music. I do not sing

traditional songs. Those songs already have a life of their

own. My songs are contemporary expressions of my traditional

Navajo culture. Now I walk forward in beauty with my music,

and with my grandfather’s words. He gave me my confirmation.

|

|

|

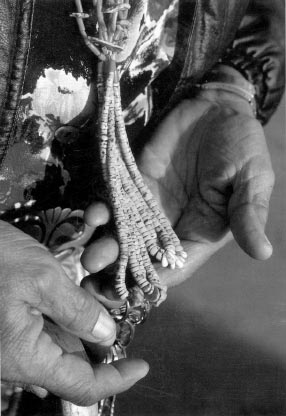

My

aunt Sadie is a jeweler and silversmith who learned

her trade from my grandfather’s brother. Turquoise

and silver work, which came from the Spanish, are important

elements of Diné art and commerce and vital to

our identity.

|

|

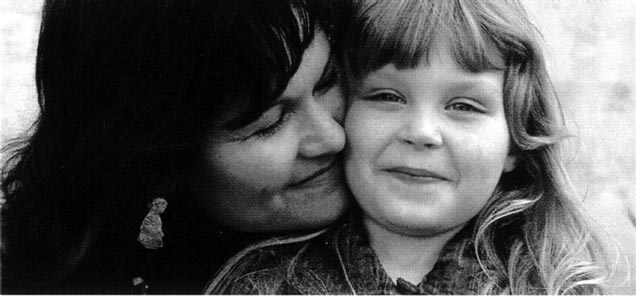

My daughter, Kelsey, is Scotch-Irish on her father’s

side and so I gave her an Irish sounding name. Her grandfather

gave her the Navaho name “T’aa Nabah” which

means “warrior who will always return home.” My

three-year-old son also has two names. His Scotch-Irish name

is Conner and his Navaho name, “Shush Yazh,” means

“little bear.”

Today, I raise my two children with the same values I was

taught. Children grow up so quickly, so I try to nurture them

as much as possible while they’re little. Nurturing and

loving our children sets the foundation for their lives so

they can feel totally bonded and secure and grow up to be

self-assured, strong and confident adults. I feel that these

days we expect children to do things by themselves at such

a tender young age without giving them this proper foundation.

We expect a baby of a few months old to help himself go back

to sleep. My instincts are to sleep with my babies until they

are comfortable enough to sleep alone and to separate gradually

as they reach an age of understanding and knowing. In my family,

we were cradled and very closely cared for until the age of

four or five. My three-year-old son still drinks from a bottle.

This is part of his nurturing.

My youngest sister, Sheila, is pregnant with her first child.

She talks about the little baby inside of her that is growing.

My three-year-old son feels like he has that baby inside of

him growing also. He walks around with my sister saying, “My

baby is growing too,” or “My baby is hungry right

now.” He feels in sympathy and is one with her. It is

good that he feels what a woman is feeling in pregnancy. When

my sister is sick and lies down, he lies down too and says

he is sick because the baby is making him tired.

My mother told us that my grandmother used to say, “Hold

good thoughts, rub your belly often and project goodness all

around when you are pregnant.” We tell Sheila not to

watch scary movies, and not to get angry or upset too much

during this time. She is doing very well. She naturally has

a good heart and enjoys the good life around her.

This focus on new life helps us all to think good thoughts

now. This is a very tough time in our family because my sister

Shannan is going through a divorce. She did all she could

to save her marriage and we all know that she is a very caring

and loving person. Our entire extended family is affected

by the divorce—we feel her sorrow, her broken heart and

her strength. She is a strong woman and inspires us all with

her bravery and courage during this challenging time. Because

I come from a nurturing family, I forget that many people

don’t have the same support. There are people who feel

all alone in this world full of people. It is unfortunate

that it should be that way, but I also know that we all have

a unique path to walk.

I try to understand the challenges in my life and know that

the only way I can grow and learn is to be kind to all life.

I believe that in our essence, our spirits are positive, pure

and loving. My mother told me that shortly before my grandfather’s

passing, he saw a rainbow. He spoke to himself as if he was

part of the rainbow and told my mother not to be afraid. “Everything

turns back to good.” This is interesting to me because

I wrote a song called Yazzie Girl several years ago about

my mother and grandmother. In that song, I say that grandmother

reminds me of the rainbow. Every time I see a rainbow, I know

grandmother is nearby. When grandfather equated himself with

the rainbow I felt he was communicating with grandmother.

My German grandmother just passed on a couple weeks ago at

age ninety-three. The day before her passing, my sister and

I were driving and noticed a rainbow in the sky—directly

before us. There were no rain clouds, just a beautiful sky.

We marveled at this rainbow and admired the beautiful colors.

Later, I learned that grandmother was then beginning to make

her journey to the other side.

My sister, Sheryl, also reminds me of the rainbow—probably

because she is so colorful and full of life. She is now thirty

years old. Years back, doctors told my parents she would never

be able to walk or verbally express her needs, but she proved

them wrong. Now she can walk and communicate her needs just

fine. A lot of credit goes to my youngest sister for teaching

Sheryl so much. At first Sheila didn’t realize the important

role she was to play in Sheryl’s life, but now she feels

good about the trials and tribulations she experienced during

the crucial first years of their lives together.

Sheryl doesn’t look or act intelligent by society’s

standards, but she is very aware of people and her surroundings.

She is spontaneous and not at all superficial. She cries,

laughs and jokes when she wants to. Some years ago, Sheryl

and I went to see Paul Simon with some of my friends. He had

just come out with the Graceland album and was touring with

African singers and dancers. People at the concert were sitting

quietly, when all of a sudden Sheryl spurts up out of her

chair and begins jumping. When Sheryl dances she jumps—her

feet leave the ground. That is her way of expressing what

she feels from the music. The more she likes it, the higher

she jumps. Sheryl was jumping so high she was stepping on

people’s feet and blocking the views of the people behind

us. I felt embarrassed. She was so energized and excited about

the dancers that she nearly jumped out of her body. There

is a lot to be enthused and excited about in this life! I

wrote a song called Earth Child for Sheryl. It acknowledges

her beauty and innocence.

Sheryl has inspired me and motivated me to help others. I

have worked in special education now for over twenty years.

I worked as a volunteer at her school during my high school

years and, during college, I worked part time at a group home

for developmentally disabled women. While on summer break

from college, I went home to visit my family and found a summer

job working with a special education program in Vallejo. I

stayed there for the next ten years. After I married and my

husband and I moved to Santa Rosa, I found a similar program

there and transferred. Recently I have taken a break because

it became too much to juggle working, traveling and performing

with raising two children and managing a family. I miss my

friends at the program and think of them often. Perhaps soon

I will return.

Working to help others is what my life is about. My fear is

that advances in technology may replace some of that. When

we become a society that is perfect we won’t have the

patience with those who need the help. Human caring and hands-on

work with developmentally disabled and the elderly is important

as well as our acceptance of human error. To be human is to

make mistakes, and to make mistakes is to learn and grow.

Sharon Burch lives in the Santa Rosa area with her husband and two children. She travels and performs her music throughout the United States, Europe and Japan and always enjoys returning to the Navajo reservation to perform for her people. Her first album The Blessing Ways was made with A. Paul Ortega, a well-known Mescalero Apache folk singer. In her subsequent three albums, she performed as the solo artist: Yazzie Girl, Touch the Sweet Earth, and Colors of My Heart. In l992 she won an EMMY for original music in a documentary and in l995 won the National Association for Independent Record Distributors INDIE Award for Native American Music.

COLORS OF MY HEART

by Sharon Burch

I want to draw the world the way that I feel,

With corn pollen sprinkles and

the colors of my heart,

The orange feeling of daybreak,

The warm red feeling of the sun,

The cool blue mist of the ocean and

the big blue sky,

The black of the night when day is done.

Yes, I’d want to draw the world the way

that I feel,

With corn pollen sprinkles and

the colors of my heart,

The taste of brown comes from our Mother Earth,

The green smells of the plants and trees,

The yellow haze of the afternoon light

Which reminds me, too, of the yellow moonlight.

Yes, I’d want to draw the world the way

that I feel,

With corn pollen sprinkles and

the colors of my heart,

The purple touch of the stormy rain showers

And the pure white air that I breathe and live by.

Yes, I’d want to draw the world the way that I feel,

With corn pollen sprinkles and

the colors of my heart.

Formerly:

Copyright © 2001 Grace Millennium